Clients sometimes contact us with questions about industrial contract strategies. What’s the best option, and what are the differences between them? What are the risks involved in each one? Achieving success on your project depends on several important decisions and factors throughout the lifecycle of a project – and one of these is choosing the right contract strategy. Tom Morten and Ingeborg Vanloon lend us a hand and summarise the various contract strategies in the industrial sector. If you’re looking to start a new project and wondering how it should be structured, read on!

The contract strategy defines the way the delivery of a project is structured into packages and the types of contract used for each package. The right contract strategy will help you achieve your project objectives while keeping within the project constraints. Using the wrong strategy will likely increase the cost, risk and time it takes to complete your project.

Contract strategies

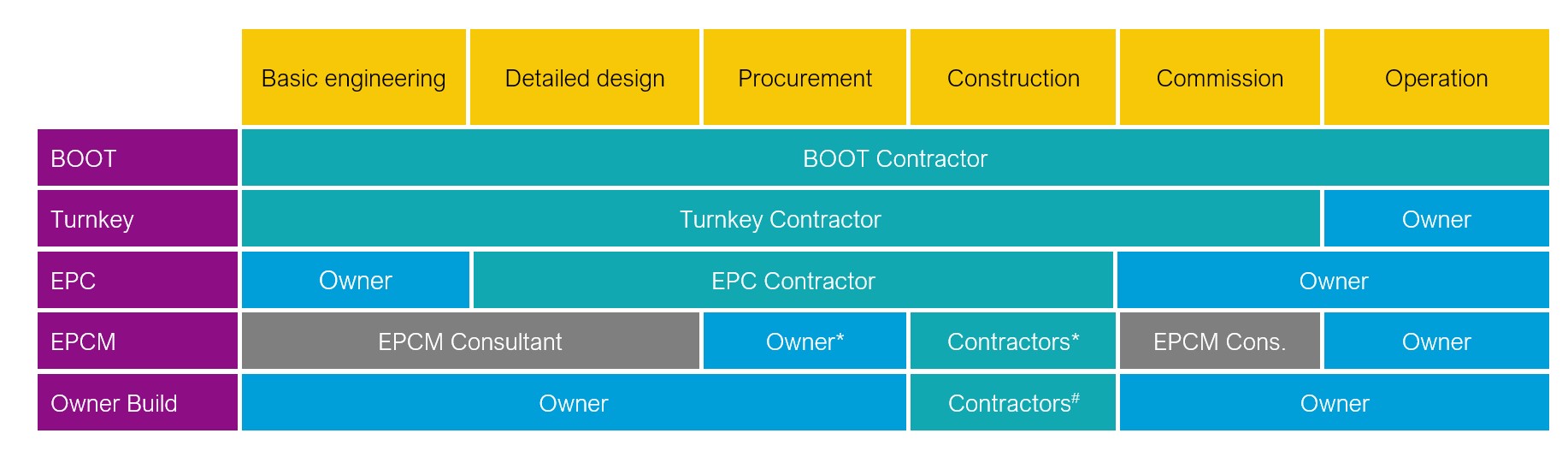

Here are five commonly used strategies for industrial projects (Table 1), showing who leads each stage. Strategies are arranged with those where the contractor takes the largest role at the top. It’s also worth noting that all of these approaches are used in other sectors as well, with some variations and different terminology.

Table 1. Common industrial project contract strategies.

* Managed by the EPCM Consultant, # Managed by the Owner

Build, Own, Operate and Transfer (BOOT) is where the Owner prepares a supply specification and then contracts a BOOT Contractor to design, fund, build and operate a plant that meets that supply specification. The Owner will pay a fee for the service provided by the BOOT Contractor and, at the end of the agreed contract period, the ownership of the facility transfers to the Owner. This minimises the upfront cost to the Owner and is often used for utility supply like the supply of industrial gases from an air separation plant or electricity from a solar farm.

More commonly, the Owner funds the project and operates the plant after commissioning.

Engineer, Procure and Construct (EPC) and Turnkey are similar, and the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. The engineering, procurement and construction is completed by the Contractor, but the funding and plant operation are by the Owner.

- Turnkey - the Contractor completes basic engineering and carries greater responsibility for design achieving the Owner’s requirements.

- EPC - the Owner completes basic engineering, and the EPC Contractor only completes detailed design with less design responsibility.

Turnkey works well when there is a well-established contractor capability for the type of project, and the Owner is less concerned with how their required functionality is achieved, for example, for large pieces of proprietary equipment such as packaging lines. EPC is better when the Owner wants more control and/or can define the requirements in more detail.

Engineer, Procure, and Contraction Management (EPCM) is where the Owner contracts an EPCM Consultant for design, procurement assistance, and construction/commissioning management. The Owner also procures the equipment and materials and engages construction contractors, managed by the EPCM consultant. This allows for a smaller Owner’s team and uses the EPCM consultant’s expertise and resources.

Owner Build - the Owner self-performs design and project management, funds the project and engages contractors for construction. This maximises Owner control and, if managed well, reduces the overall project cost.

Hybrid strategies are possible and sometimes different strategies are applied to parts of large projects. A combination of EPC and EPCM are the most common strategies for industrial projects.

Project objectives and constraints

Each project is different, and the objectives and constraints will affect the selection of strategy. These include the following.

Project budget: Projects must be delivered within the budget that justifies completing the project and that the Owner can fund. Strategies with greater risk transfer to consultants or contractors will increase the project cost.

Project schedule: Lead times for large equipment or bespoke plant (the time to design equipment, order materials, fabrication, assembly, testing and shipping of equipment to the project location) often drive the project schedule. To deliver a project on-time with long equipment lead-times, equipment may need to be ordered early. Owner Build and EPCM (with the Owner directly purchasing equipment), allow orders to be placed sooner than strategies where contractors order equipment. BOOT or Turnkey require the main contractor to be engaged very early to start design and to order equipment. Owners should consider whether they can finalise their requirements and form contracts this early.

Market capability: Within New Zealand, there is limited industrial contractor capability to reliably deliver using BOOT, Turnkey and EPC strategies. While a few types of projects routinely use these methods (such as milk spray dryers or “standard” industrial buildings), our industrial market is generally too small. International contractors can be enticed to bring their financing and expertise for very large projects, however they are often less interested in smaller projects. This can be surprising to international Owners who are looking to complete projects this way in New Zealand and find that strategies they use in Europe or the US are not available here.

Before adopting a BOOT, Turnkey or EPC strategy, our recommendation is to check that there are contractors in the market who understand these strategies and are interested in taking on the work. If an Owner selects a BOOT strategy, they need to quickly identify the BOOT supply requirements ready to tender and be prepared to negotiate a contract for a long “service” duration.

Owner’s experience and capacity: An Owner Build strategy allows the project scope and requirements to be refined through basic engineering and detailed design but requires a much larger Owner’s team. The owner can engage an EPCM Contractor to reduce the demand for in-house capability. Generally, in New Zealand, industrial companies have reduced their in-house capacity and capability to design and manage large projects over the years and rely more on contractors (including EPCM Consultants) to assist with this. We recommend that Owners review their in-house capacity and capability to check that they can support their chosen strategy, and develop a resourcing plan to fill any gaps before they cause delays.

Project ownership and risks

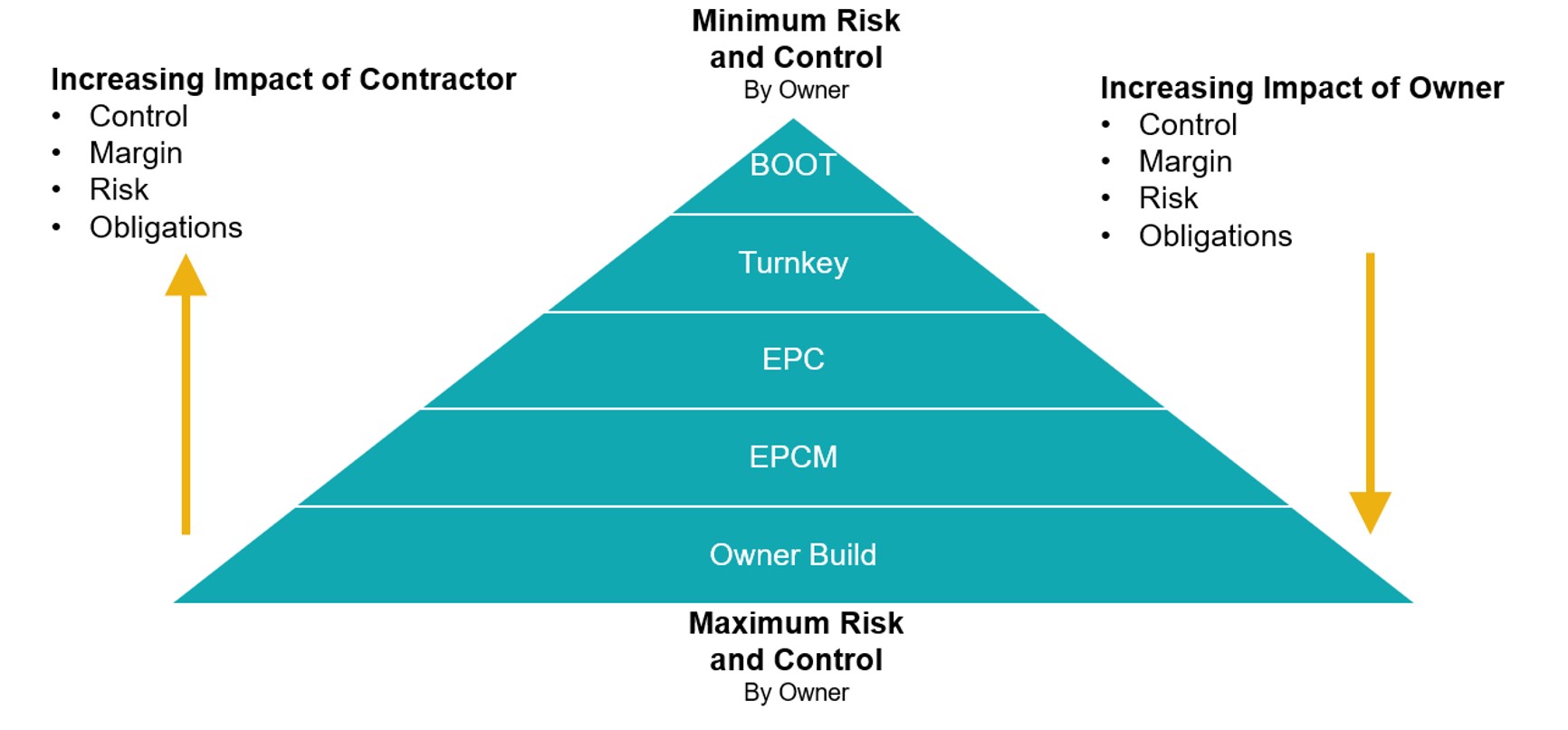

As mentioned earlier, contract strategies at the top of Table 1 transfer more project risk from the Owner to the Contractor, and they charge more for taking on this risk. Strategies towards the bottom keep more risk with the Owner and, if everything goes well, cost less. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Risk and control allocation of different contracting strategies.

If a strategy tries to transfer risks that Contractors cannot understand or manage, then Contractors may decline to tender or submit non-complying tenders (such as excluding engineering and procurement from an EPC tender). If they do submit complying tenders, the premium they include to cover their real and perceived risk might be much higher than an Owner can accept.

It is important for an Owner to thoroughly investigate the capabilities of Contractors before and during the tender process to ensure that the Contractor can take on the required ownership and risk. If this is not checked, it can lead to a false sense of security and, if the Contractor fails to manage the risk effectively, failure of the project and significantly increased costs.

Contracting structures

Each contracting strategy allows for different contracting structures to break down the work into various packages, providing flexibility to the Owner to apply a structure that suits the project, their capabilities and objectives.

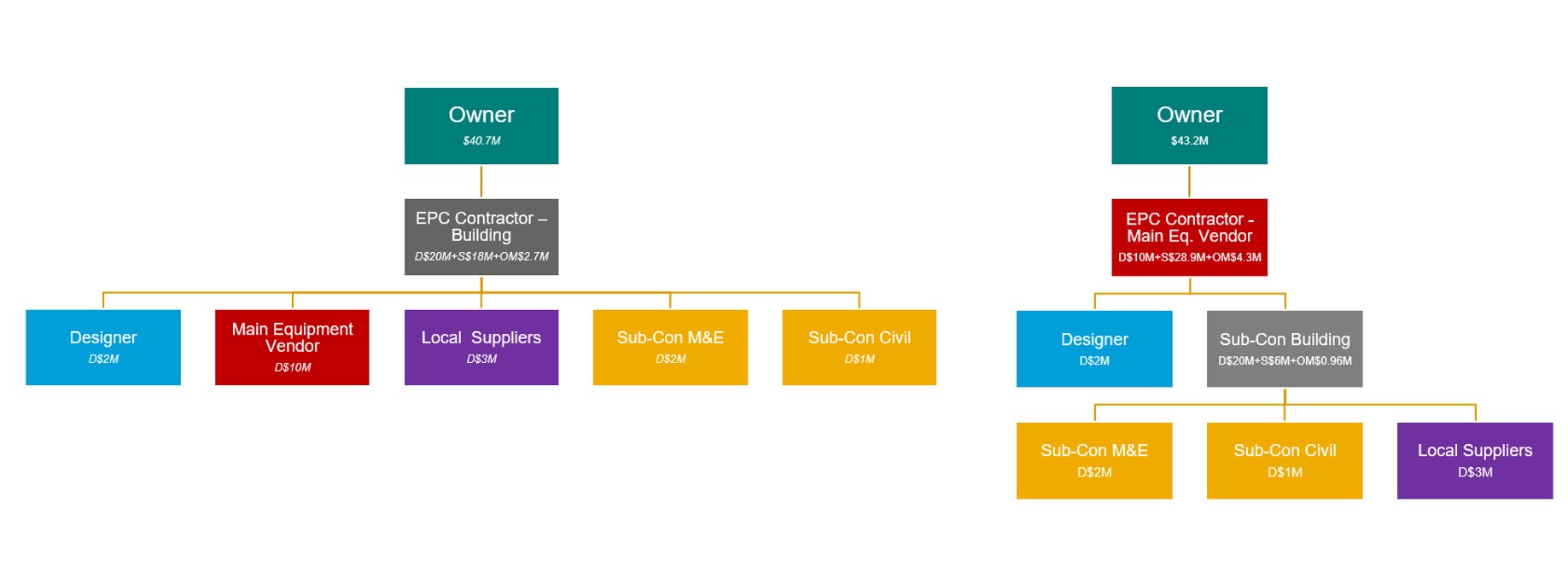

For instance, an Owner could form an EPC contract with the main Contractor being the building Contractor (who subcontracts the main equipment vendor and others) or the main Contractor being the main equipment vendor (who subcontracts the building contractor and others) as shown in Figure 2. The project scope and local capabilities will determine which Contractor is best suited to take the role of the main EPC Contractor.

Figure 2. Comparison of Building Contractor-led and Main Equipment Vendor-led EPC contracting structures.

The EPC Contractor will subcontract work they do not self-perform, adding their management overhead and margin on that work. These costs can add up, particularly when there is a long subcontract chain with compounding overhead costs and margin. Example costs of the two different structures are shown in Figure 2, including direct contractor costs (D), subcontractor costs (S) and overhead and margin (OM) estimated as 15% of subcontractor costs. These different structures change the total project cost by more than 5% with no change in project scope and the same contractors performing the physical work.

Sometimes subcontracts are not prepared with the same rigour as head contracts. This can make it difficult for Owners to hold subcontractors or vendors accountable if there are problems with their equipment or construction works, so it is vital that the contract conditions clearly define the roles and responsibilities of all parties.

It is important for Owners to understand Contractor capabilities and their proposed contracting structures to keep contract/subcontract chains short. Supply of equipment and construction with significant costs or risks should be near the top of the contracting chain.

Selecting a contract strategy

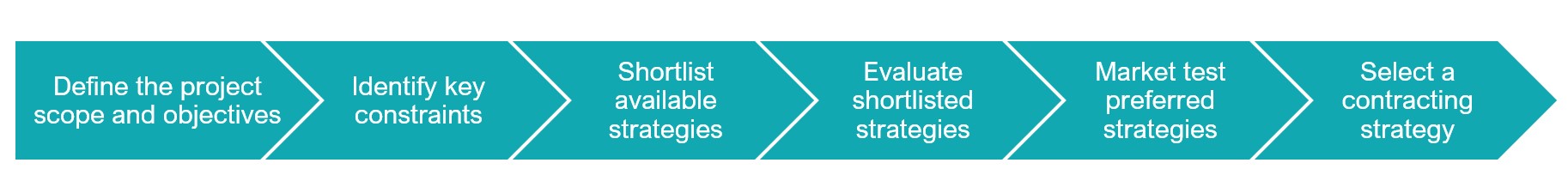

Selecting the right contract strategy could be as simple as reusing a strategy that worked well on a similar project. But even if projects are similar, an Owner should check their contracting strategy to confirm it is right for their project. Evaluation and selection should include steps in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Steps to evaluate between different contract strategies for a project.

Changing strategies during the project is possible when managed well, but risks additional costs or delays (such as from re-tendering or redesign). Contractors can become confused or lose confidence in a project and decline to re-tender.

Conclusion

It is important to evaluate the contracting strategy for all projects early and understand the market’s capabilities. Transferring risks to Contractors can pay off for a project but will cost more.

If you are familiar with all the acronyms and wondering why we missed BOO and did not differentiate between EPCM and EpCM – or if you are feeling a little lost – please get in touch so we can figure out your project’s constraints and select the most appropriate contract strategy for your project. We have assisted many clients with developing and implementing a well-considered contract strategy.

New Zealand

New Zealand

Australia

Australia

Singapore

Singapore